The fourth-most-read post on Boots Theory last year questioned a pretty strongly-rooted tenet of modern Labour Party faith. People have said to me since the election result, “see, it worked!” Yet National still gained 44.4% of the vote, and Labour’s boost came directly from Jacinda Ardern’s amazing personal appeal. And the question now becomes: is winning one election worth it if we don’t actually change the status quo?

Originally published 25 March 2017

Labour and the Greens have announced a cornerstone coalition policy for the 2017 general election: a set of Budget Responsibility Rules which will, per the Greens’ website:

… show that the Green Party and the Labour Party will manage the economy responsibly while making the changes people know are needed, like lifting kids out of poverty, cleaning up our rivers, solving the housing crisis, and tackling climate change.

It feels like I’ve been banging my head against this brick wall for a decade. The short version is this:

Labour and the Greens cannot credibly campaign on a foundation of “fiscal responsibility”. It is anathema to genuine progressive politics. It isn’t a vote-winner. It’s a vote-loser.

I’ve heard the defence: but we ARE the fiscally responsible ones! Look at our surpluses in government! Witness our detailed policy costings! BEHOLD OUR GRAPHS!

If empirical evidence worked, we’d already been in government and this conversation wouldn’t be happening, and I know I for one would be happier for it.

Everyone knows this is crap. No one really tries to defend it by saying, “but fiscal responsibility is the most important thing in government”. They say, “but we need people to believe we’re fiscally responsible.” They say, “but the media always ask how much our policies will cost!” They say, “we need to win or we can’t achieve anything, learn to count Stephanie.”

We know we’re selling our souls, but only for the right reasons. The tragedy is, we’re not. Fiscal responsibility is the Bog of Eternal Stench. Once you dip so much as a toe in, it makes everything else you do reek.

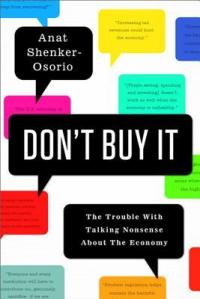

Don’t just take my word for it – after all, we’re all rational creatures making objective decisions based on evidence, right? Take it from someone who has the evidence, my favourite American Anat Shenker-Osorio:

Peer-reviewed psychological studies show that money-primed people … become more selfish. They are, for example, much less willing to spend time helping another student pretending to be confused about a task. When an experimenter dropped pencils, money-primed subjects elected to pick up far fewer than their unprimed peers. Also, when asked to set up two chairs for a get to know you chat, those who had money put on their minds placed the chairs farther apart. Money-primed undergrads showed greater preference for being alone.

The results of these experiments should give progressives pause and serve as lessons for how we do our messaging. Talking about money first makes the whole subsequent conversation start in a mean and selfish place — the last thing we want when we’re talking about the common good and our national future. …

Those politicians who actually believe in the institution in which they serve would do far better to speak of what government does for us — and trust that we’re smart enough to know that good things don’t come cheap.

If we prompt New Zealand voters to think about money first, they aren’t going to think about common good, about ensuring their neighbours have a good life too. They’re going to think “actually, getting another block of cheese each week does sound good” and the right’s fourth term is secured. They don’t even have to work for it, because when we explicitly buy into their values, it weakens our own.

It cuts out the heart of our politics. Our critics are absolutely right: Labour and the Greens are not trusted to be good fiscal managers. THAT’S THE POINT. No one wants us to be good fiscal managers – except for the right, who are thrilled that we not only want to play in their playhouse but will obey all the rules they’ve made up to ensure they always win.

It’s like some people watched Mean Girls and thought, “well of course we have to wear pink on Wednesdays and throw out our white gold hoops, how else will we get Regina George to truly respect us?”

Pink is not our colour. Fiscal responsibility is not our strength. The economy is not the most important thing in the world – HE TANGATA, HE TANGATA, HE TANGATA.

We’re meant to be the ones who care about people, and make sure everyone in our communities is taken care of, whether they’re sick, or old, or exploited by a shoddy employer or having a baby or building a life in a new country. These are the areas where we’re strong. These are the values which we must promote – not just because we hold them dearly, but because doing that is the best way to fuck up the other side’s message of greed and self-interest and exploitation of people and our planet.

People want change. They don’t want poverty and housing crises and public services stretched to breaking point. They know these things cost money! But they’ve been told for decades that government must be small, and the private sector runs things better, that the only metric that matters is that sweet surplus. They know it doesn’t feel right, but there doesn’t seem to be another way of doing things, because we keep telling them we agree with it. And they vote for the party they “know” are the better economic managers, because that’s National’s brand, and not all the graphs and spreadsheets we throw at them are going to convince them otherwise.

We’re never going to win while we keep playing in the right’s playhouse and skinny-dipping in the Bog of Fiscally Responsible Stench because we want to smell just like our enemies. We have to be an alternative. Stop talking about the bloody money and start talking about people.